Cinema & Architecture: It could be argued that there exist essential intersections in these two practices. Both represent different expressive means yet with the same reference systems when it comes to space; they both articulate lived space, which is experienced and understood in sequences, making use of powerful visual language. In this article I would like to share some of the cases where cinema and architecture meet and discuss briefly some examples.

///

Cinema e architettura: si potrebbe sostenere che esistono intersezioni essenziali in queste due pratiche. Entrambi rappresentano diversi mezzi espressivi ma con gli stessi sistemi di riferimento quando si tratta di spazio; entrambi articolano lo spazio vissuto, che viene vissuto e compreso in sequenze, facendo uso di un potente linguaggio visivo. In questo articolo vorrei condividere alcuni dei casi in cui cinema e architettura si incontrano e discutere brevemente alcuni esempi.

SETTING: NOT JUST A BACKDROP

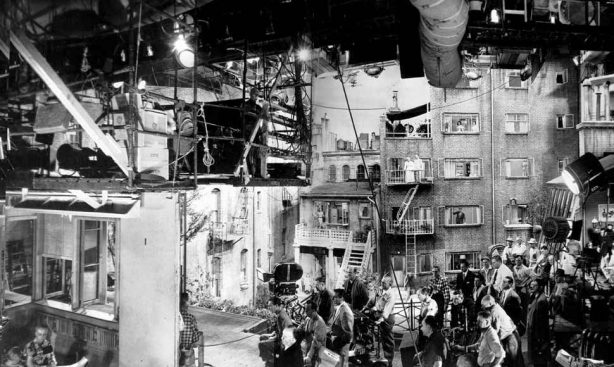

a.La notte (1961) directed by M.Antonioni- b.Set construction for ‘The rear window’ directed by A. Hitchcock (1954)

Antonioni often used buildings of the modern movement in order to transmit emotions of alienation and desperation. In a similar way, in Godard films, images of the city are used as metaphors for everyday situations in the life of the protagonists. | Hitchcock once stated that, ‘a rule I’ve always followed is: never use a setting simply as a background. Use it 100%. You’ve got to make the setting work dramatically. In other words, the locale must be functional (1)’.

Going back to 1895, when Lumière brothers and George Méliès started screening their first films, two basic guidelines can be depicted: The former used the city as a background for their movies, while the latter constructed sets and used special effects for his shots. Yet, in both cases the scenery was not just a ‘backdrop’ but became part of the film’s narrative. Therefore, we could make a distinction between films which actually make use of ‘real space’ and those which ‘create artificial spaces’ for their needs. Films like Roma Citta Aperta (1945), Ladri di Biciclette (1948) could be viewed as characteristic examples of the first category while Der Golem (1920) and Metropolis (1927) of the second.

///

Nel lontano 1895, quando i fratelli Lumière e George Méliès iniziarono a proiettare i loro primi film, si possono rappresentare due linee guida fondamentali: i primi usavano la città come sfondo per i loro film, mentre il secondo costruiva scenografie e utilizzava effetti speciali per i suoi scatti. Eppure, in entrambi i casi, lo scenario non era solo uno “sfondo”, ma divenne parte della narrativa del film. Pertanto, potremmo fare una distinzione tra i film che effettivamente utilizzano lo “spazio reale” e quelli che “creano spazi artificiali” per i loro bisogni. Film come Roma Città Aperta (1945), Ladri di Biciclette (1948) potrebbero essere considerati esempi caratteristici della prima categoria, mentre Der Golem (1920) e Metropolis (1927) del secondo.

In 1927, Luis Buñel expressed that cinema is ‘the faithful translator of the architect’s most daring dreams (2)’. The previous statement underlines this special relation between these two practices: Cinema, freed from the functional and physical constraints which characterize the second, can go even further in terms of spatial experiments providing as a result unique sensory experiences.

///

Nel 1927, Luis Buñel ha affermato che il cinema è “una fedele traduzione dei sogni più audaci dell’architetto”. La dichiarazione precedente sottolinea questa relazione speciale tra queste due pratiche: il cinema, liberato dai vincoli funzionali e fisici che caratterizzano il secondo, può andare oltre in termini di esperimenti spaziali fornendo come risultato esperienze sensoriali uniche.

THE DRAMA OF SPACE

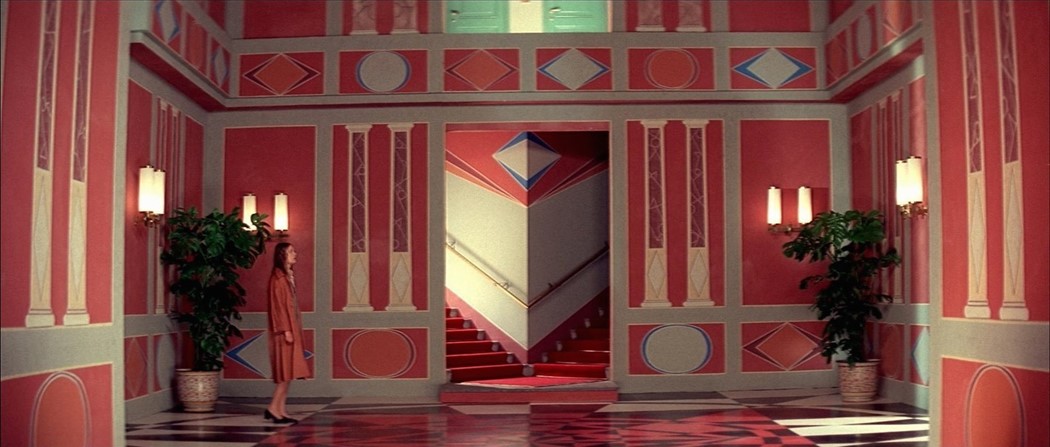

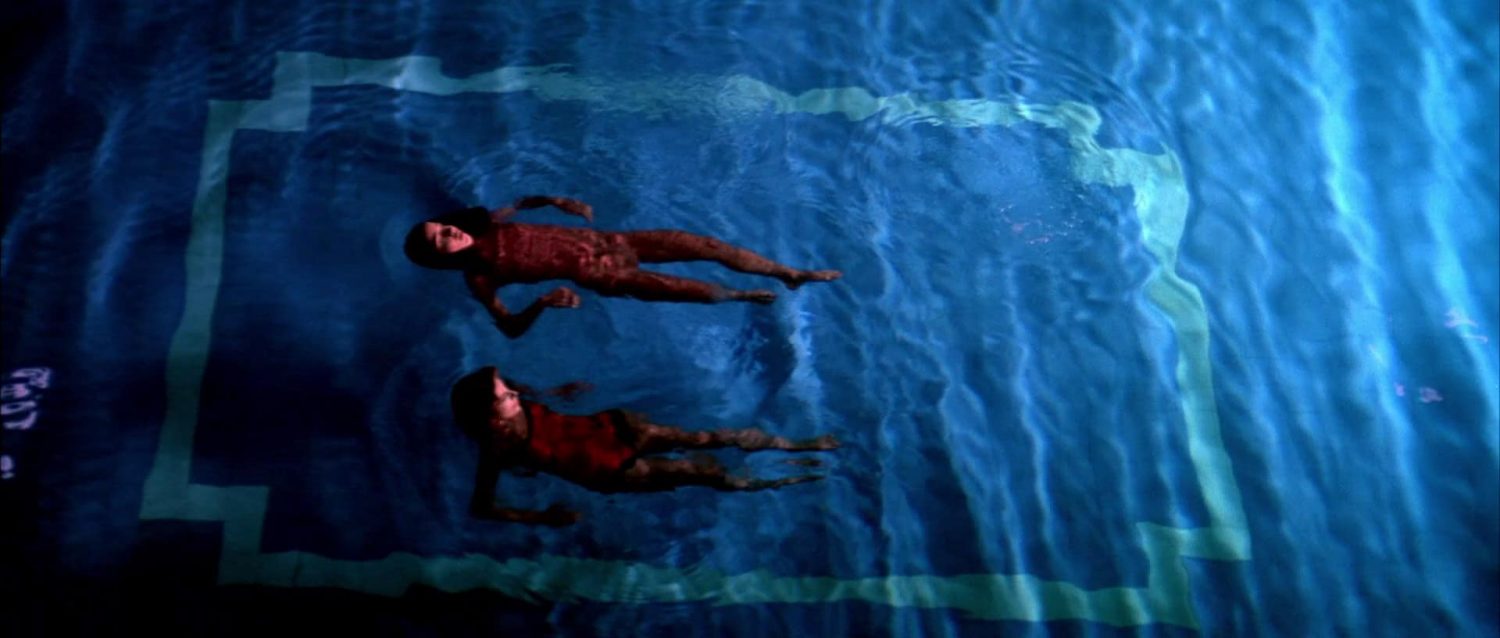

As discussed before, specific spaces are selected or created as sets for a movie because of their symbolic dimensions. This can be further illustrated by the next example: In Dario Argento’s film Suspiria (1977), symmetry is used as an element of terror itself, which creates anxiety through its absolute order, or terror through a sudden transition to disorder- thus giving the impression of dissolution and death (which is what actually happens when a glass roof breaks and a girl falls from it, hanging from a rope: as the vitro window breaks and she falls, its symmetrical shape turns into randomly broken pieces). Other elements, such as water3, are used to visualize sentimental confusion and agitation. In the swimming pool scene for example, the girls’ gentle moves disturb the calm water surface creating a contrast between the shape of the water and the strict geometric shape of the pool (perhaps also aiming to provide a claustrophobic sensation).

///

Come discusso in precedenza, gli spazi specifici sono selezionati o creati come set per un film a causa delle loro dimensioni simboliche. Ciò può essere ulteriormente illustrato dal prossimo esempio: nel film di Dario Argento Suspiria (1977), la simmetria viene usata come un elemento del terrore stesso, che crea l’ansia attraverso il suo ordine assoluto, o il terrore attraverso un’improvvisa transizione al disordine, dando così l’impressione di dissoluzione e morte (che è ciò che accade quando un tetto di vetro si spezza e una ragazza precipita, appesa a una corda: mentre la finestra di vetro si spezza e cade, la sua forma simmetrica si trasforma in pezzi spezzati casualmente). Altri elementi, come l’acqua, sono usati per visualizzare confusione e agitazione sentimentali. Nella scena della piscina, ad esempio, le dolci mosse delle ragazze disturbano la calma superficie dell’acqua creando un contrasto tra la forma dell’acqua e la rigida forma geometrica della piscina (forse anche mirando a fornire una sensazione claustrofobica).

EMOTION IN MOTION

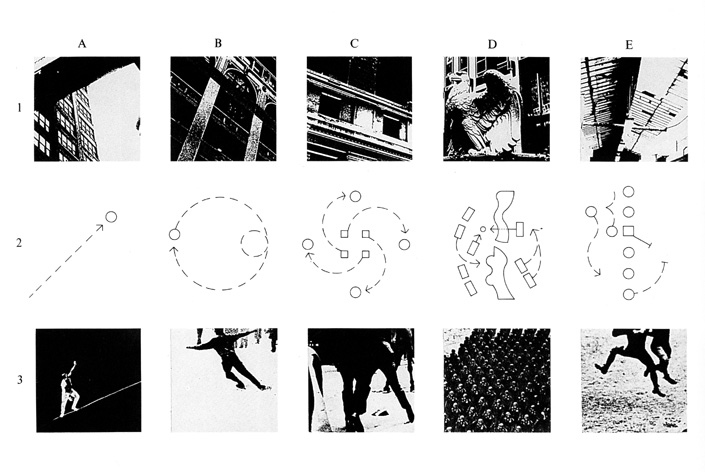

e. Competition project by OMA for Jussieu Library (1992) - f. The Manhattan Transcripts 1976-1981

Jean Nouvel once asserted that: ‘Architecture exists, like cinema, in the dimension of time and movement. To erect a building is to predict and seek effects of contrast and linkage bound up with the succession of spaces through which one passes (4)’. The previous statement underlines the temporal and spatial structure of both cinema and architecture and the kinesthetic way which is applied in order to experience and understand both of them. Architects often borrow cinematographic terms (e.g. script, plot, montage, frames) in order to describe the effects or the atmosphere they want to transmit in their buildings. For example, in Rem Koolhaas’ and Bernard Tschumi’s buildings there is a permanent quest for a constant contact with different ‘episodes’: In the competition for Jussieu Library (1992), the OMA project could be viewed as a vertical landscape where the elements of the libraries are reimplanted in the edifice like buildings in a city and where the interior spaces serve ‘not as a collection of rooms, but as a series of incidents5’. Respectively, the three organization elements6 in Villette’s Parc (1987) can be better understood if regarded as film sequences; not as self-contained images. Their final meaning is cumulative- it does not depend merely on a single frame (such a façade), but on a succession of frames or spaces (7).

///

Jean Nouvel una volta asseriva che: “L’architettura esiste, come il cinema, nella dimensione del tempo e del movimento. Costruire un edificio significa immaginare e creare effetti di contrasto e collegamento legati alla successione di spazi attraverso i quali si passa (4)”. Questa affermazione sottolinea la struttura temporale e spaziale del cinema e dell’architettura e il modo cinestetico applicato per sperimentare e comprendere entrambi. Gli architetti spesso prendono in prestito termini cinematografici (per esempio sceneggiatura, trama, montaggio, fotogrammi) per descrivere gli effetti o l’atmosfera che vogliono trasmettere nei loro edifici. Ad esempio, negli edifici di Rem Koolhaas e Bernard Tschumi c’è una costante ricerca di un contatto costante con diversi “episodi”: nel concorso per la Biblioteca Jussieu (1992), il progetto OMA potrebbe essere visto come un paesaggio verticale in cui gli elementi delle biblioteche sono reimpiantati nell’edificio come edifici in una città e dove gli spazi interni servono ‘non come una raccolta di stanze, ma come una serie di incidenti5’. Rispettivamente, i tre elementi organizzativi6 di Villette’s Parc (1987) possono essere meglio compresi se considerati come sequenze di film; non come immagini autonome. Il loro significato finale è cumulativo: non dipende solo da un singolo fotogramma (una facciata simile), ma da una successione di fotogrammi o spazi (7).

To sum up, a lot can be learned from this reciprocal relation between cinema and architecture. As architects, we can be inspired from it and as lovers of the cinema… we can enjoy it, at maximum!

///

Per riassumere, si può imparare molto da questa relazione reciproca tra cinema e architettura. Come architetti, possiamo esserne ispirati e come amanti del cinema … ci possiamo divertire, al massimo!

NOTES

1: Designboom – Steven Jacobs looks at the architecture of Alfred Hitchcock

2: The Bauhaus and America: First Contacts, 1919-1936, p.41

3: I am referring especially to the use of water because in many cases it plays a crucial, ‘structural’ role in architectonic projects.

4: Pritzkerprize – Biography Jean Nouvel

5: Wordsinspace and more on Oma.eu

6: Villette’s Parc was designed with three principles of an organization classified by Tschumi as points, lines, and surfaces. At first, the site is organized through a grid of 35 points (follies) which serve as a reference system. The lines represent movement paths which intersect and lead to various directions across the park. The surfaces represent landscaped gardens.

7: The Manhattan Transcripts, B.Tschumi, p.11

IMAGES SOURCE

a. Architecture and urban landscape in Michelangelo Antonioni’s film La Notte

b. Reddit.com

c. brg.com and fubiz.com

d. Anothermag.com and Filminquiry.com

e. Wordinspace.net

f. Tschumi.com

g. wimwendersstiftung.de

h. blog.nationalgeographic.org

i. digg.com