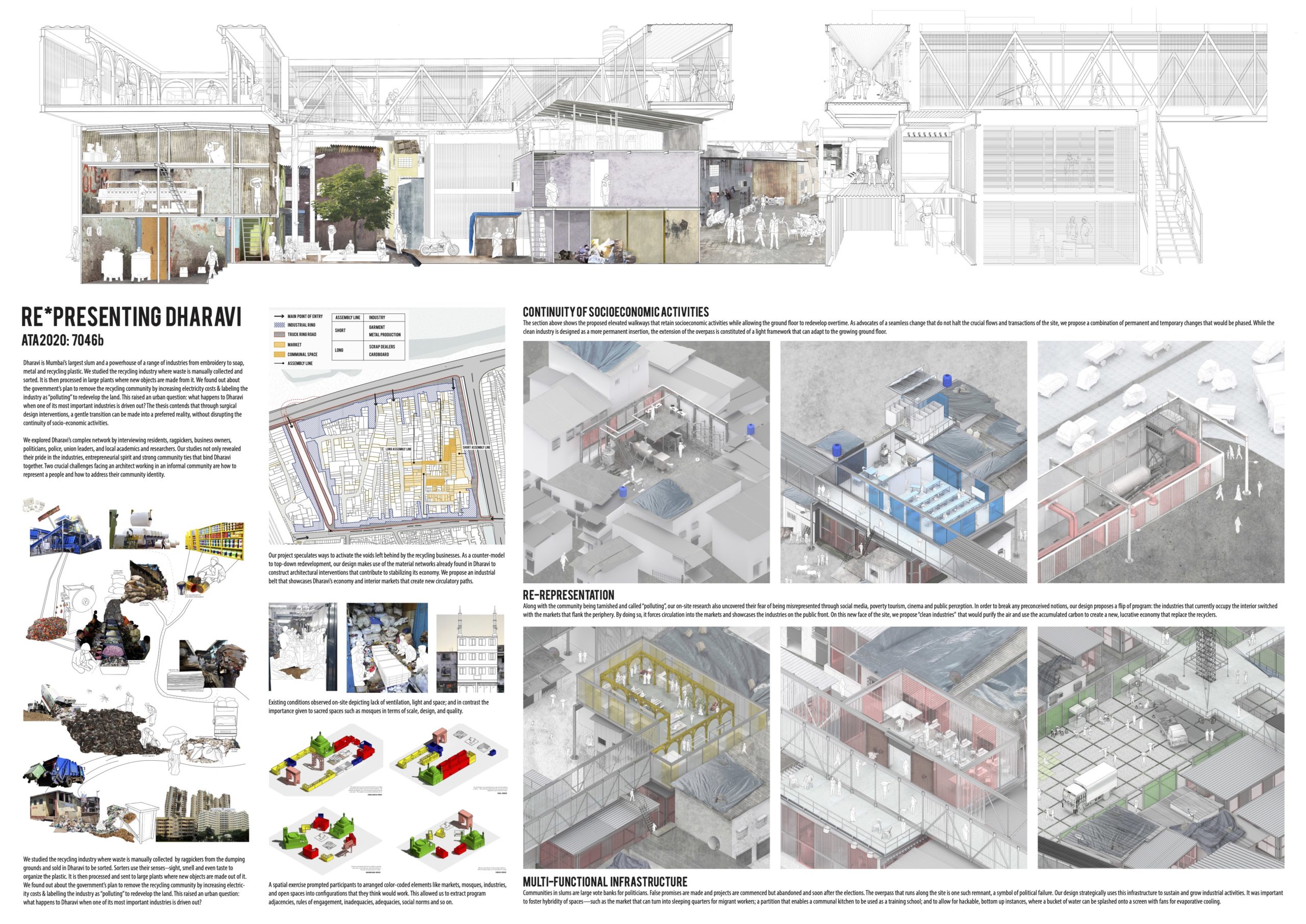

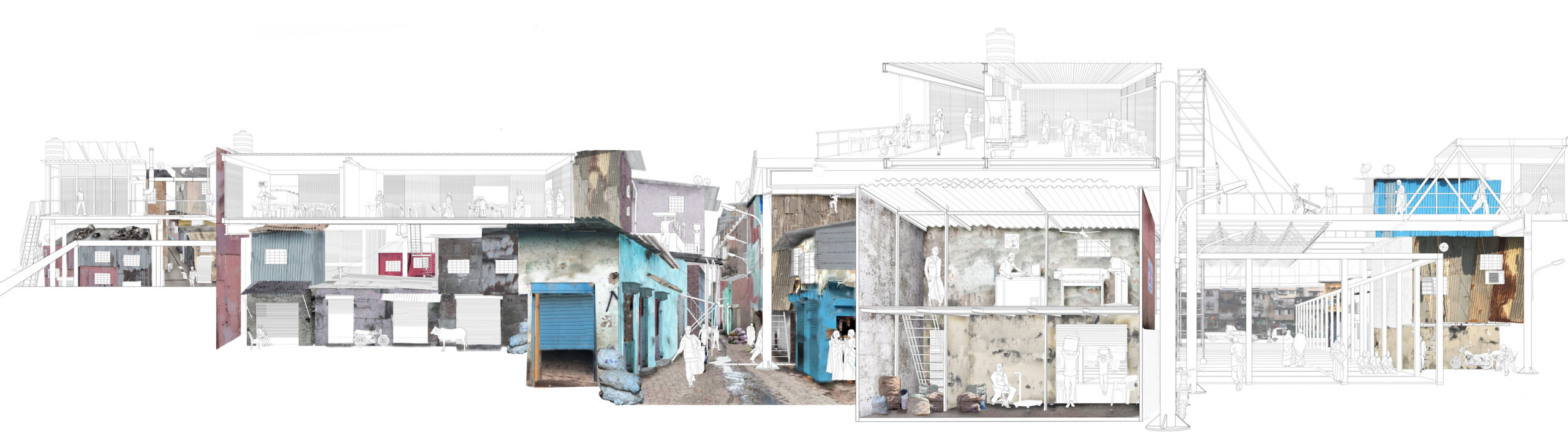

Dharavi is Mumbai’s largest slum and a powerhouse of a range of industries from embroidery to soap, metal and recycling plastic. We studied the recycling industry where waste is manually collected and sorted. It is then processed in large plants where new objects are made from it. We found out about the government’s plan to remove the recycling community by increasing electricity costs & labelling the industry as “polluting” to redevelop the land. This raised an urban question: what happens to Dharavi when one of its most important industries is driven out? The thesis contends that through surgical design interventions, a gentle transition can be made into a preferred reality, without disrupting the continuity of socio-economic activiti

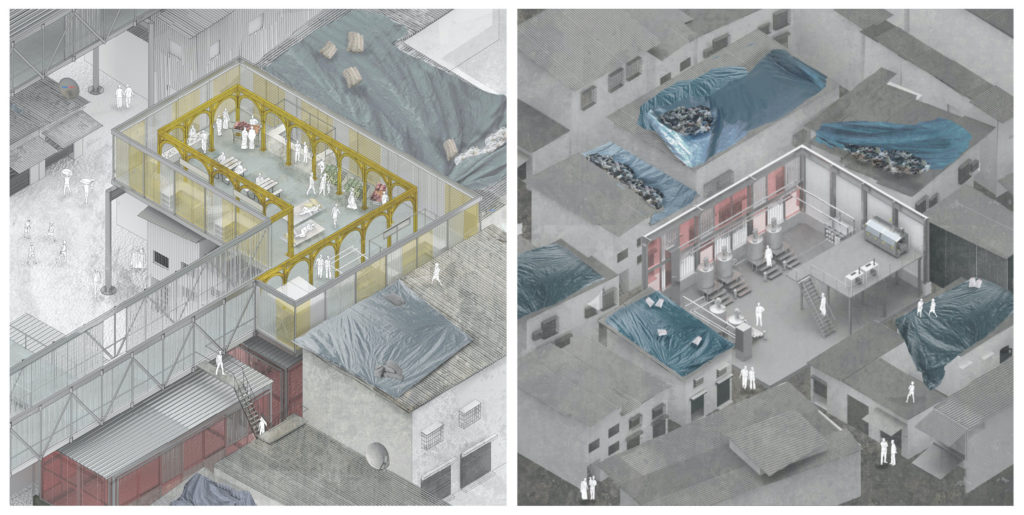

We explored Dharavi’s complex network by interviewing residents, ragpickers, business owners, politicians, police, union leaders, and local academics and researchers. Our studies not only revealed their pride in the industries and entrepreneurial spirit, but also strong community ties that bind Dharavi together. Two crucial challenges facing an architect working in an informal community are how to represent a people and how to address their community identity. Our interviews uncovered residents’ fear of being misrepresented through social media, poverty tourism, cinema and public perception. For the new face of the site, we propose “clean industries” that would purify the air and use the accumulated carbon to create a new, lucrative economy to help fill the void left by the removal of the recyclers. We also took cues from the existing conditions observed on-site. An incomplete pedestrian overpass that runs along the site is a symbol of political failure. Our design strategically branches from this infrastructure to support industrial activities by nestling social and physical amenities into the existing fabric. It was important to foster hybridity of spaces—such as the market that can turn into sleeping quarters for migrant workers; a partition that enables a communal kitchen to be used as a training school; and to allow for hackable, bottom up instances, where a bucket of water can be splashed onto a screen with fans for evaporative cooling.

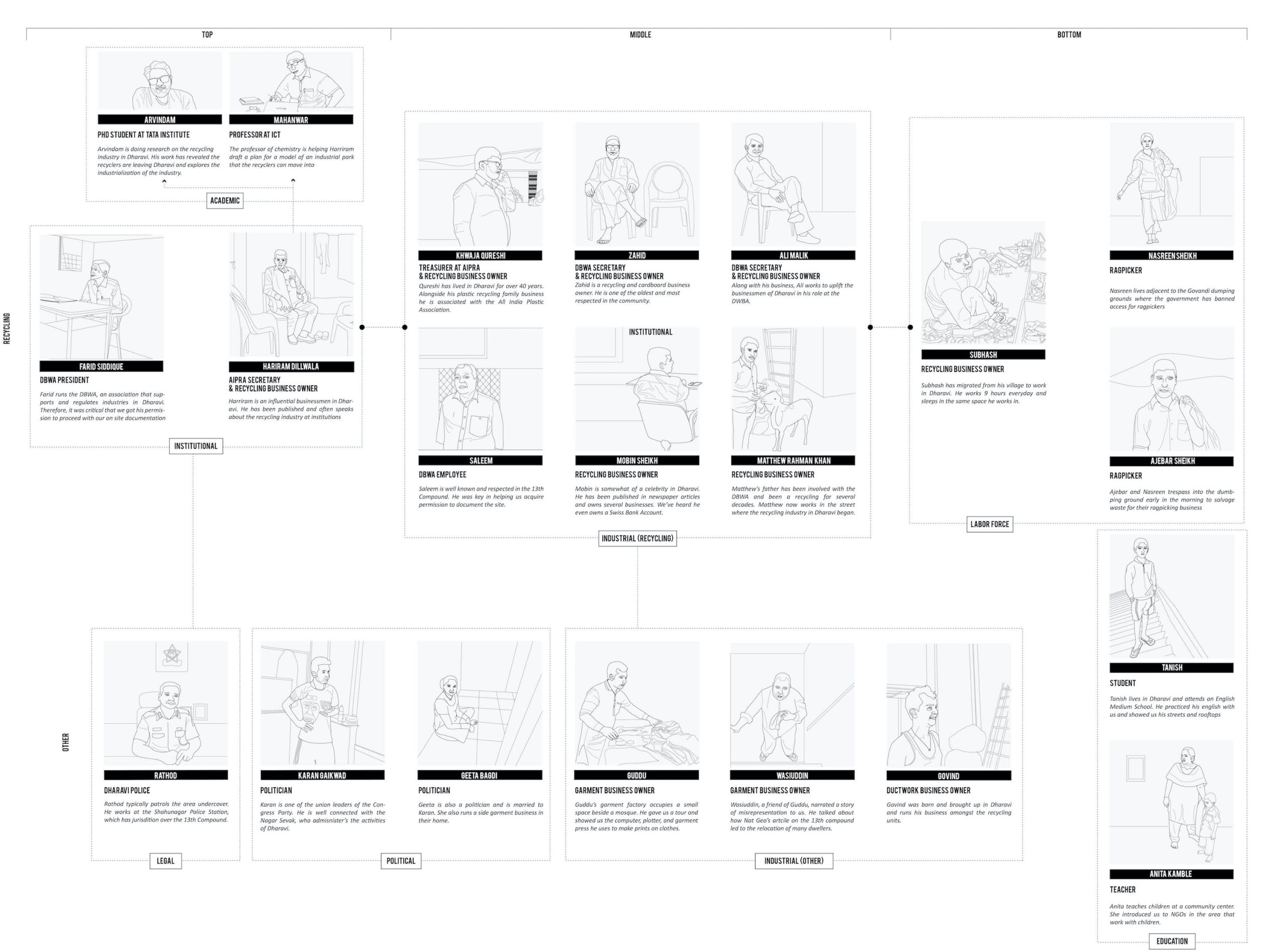

To analyze the complex network of the stakeholders we met, we organized them in the apparent hierarchies that they exist in: legal, political, institutional, industrial, and laborial. We conducted cognitive, design workshops to glean tacit knowledge embedded within the place. The workshops were intended to be visually stimulating, entertaining, and abstract enough so that the community would stray away from scripted answers and inform us of things that they would not perhaps share during an interview. In the Priority Exercise workshop, participants were asked to arrange items such as security, water, electricity--to reveal what the design should include first, and things that could come in later. A spatial exercise prompted participants to arranged color-coded elements like markets, mosques, industries, and open spaces into configurations that they think would work. This allowed us to extract program adjacencies, rules of engagement, inadequacies, adequacies, social norms and so on. We concluded our workshops with a town hall meeting and interacted with around 30 business owners to showcase our research and findings for their feedback. The process has revealed to us that architecture can work with communities to frame preferred realities. Dharavi is not just in Mumbai but exists in the favelas of Brazil, villages in Lagos and settlements in Manila. Our project proposes kernels of opportunity to such areas.

The Board: